The Fagaceae of Hong Kong

The Oaks of Hong Kong : Evolutionary and Morphological Diversity on a Continental Margin

Dr Joeri Sergej Strijk

Alliance for Conservation Tree Genomics, Kuala Lumpur, 43500, Selangor, Malaysia.

(article published in International Oaks; here released with additional photographs), No 29: p77-90, 2018. ( Click here for the homepage of the International Oak Society)

To cite, please use: Strijk, J.S. 2018. The Oaks of Hong Kong : Evolutionary and Morphological Diversity on a Continental Margin. International Oaks. No 29: p77-90. © The International Oak Society.

ABSTRACT

Hong Kong represents an intriguing example of how topography, climate and evolutionary time can combine to create a highly diverse array of environmental conditions on a small geographic scale. Located on the edge of continental Asia, it consists of pieces of mainland, islands and peninsula that were once home to warm forests with elephants, tigers and rhinoceros. Today it holds one of Asia’s megacities with a population of 7.4 million people, yet more than half of its surface area has been designated as protected green zones. These country parks, watershed reservoirs and protected upland areas hold the last populations of Hong Kong’s oak species (in addition to 24 other Fagaceae), as well as a rich and varied flora and fauna. Here I provide a brief overview of the history of Hong Kong’s forests, oaks and efforts currently underway to secure their continued survival. Finally, I present a newly recorded oak species for Hong Kong, bringing the total numbers of species found to fourteen.

Keywords: Quercus, Fagaceae, Hong Kong, China, mountains, microhabitat, population reduction, conservation, urbanization

Introduction

China ranks second in number of recognized species in the genus Quercus, with 104 species listed according to Wu and Raven (1999). This is far below Mexico with around 200 species (Trehane 2007) and contrasts with Indochina: Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam with between 55 and 60 species (Strijk, 2019a in preparation); Thailand with approximately 30 (Phengklai 2008); and Indonesia with an estimated 15 (Soepadmo and Steenis 1972). In subtropical and tropical Asia, the distribution of Quercus species is tightly correlated with higher elevation and cooler climate. Some Quercus species are restricted to lowland tropical rainforest environments (e.g., Q. kerangasensis Soepadmo (< 100 m, Borneo) and Q. merrillii Seemen (100-500 m, Borneo, Philippines) but the vast majority is either reported with wide elevational ranges (i.e., 650-1,700m) or are firmly recognized to occur only in higher elevation zones (1,000 m and up). Ecosystem preferences in widespread, speciose groups like Quercus become more apparent in regions where geography imposes spatial constraints on plant lineages and communities.

In areas where lowland conditions are rare, such as in the extensive isthmus of Kra region of Thailand, the distribution patterns of eight species of Quercus show spot occurrences for six species only in the highest habitat available (Phengklai 2008). Conversely, in areas where only lowland habitat is available, like on the island of Singapore (max. elevation Bukit Timah, 163m), only one species has been recorded, Q. argentata Korth., a widely distributed species growing from sea level to 2,700m (Chong et al. 2009). An additional 20 species of Fagaceae in two other genera (Lithocarpus and Castanopsis) are native to Singapore (Strijk, 2019b in preparation). Natural limitations in distribution can have important implications for speciation, genetic diversity and species survival of past and future populations. This is particularly poignant for extant populations of Quercus (and other Fagaceae) existing in increasingly urbanized settings, such as Singapore and Hong Kong.

The forest habitat of Hong Kong – past and present

Hong Kong is relatively small (roughly 1,100 km2), but its varied topography, volcanic foundations and resulting geological substrates are highly complex (Corlett 1992). The subtropical climate, with mild, temperate winters (but with occasional frost at higher elevation) and hot, humid summers including tropical cyclones, creates a wide range of habitat types throughout the territory (Shum 2015, Environmental Resources Management 2008). The total number of plant species found surpasses that found in the British Isles, but over a period of many centuries, nearly all of Hong Kong’s old-growth forests have been lost to lumber harvesting, tea plantations and lime-production that have taken much of the native flora and fauna (Hau et al. 2005). This has left Hong Kong, much of which is covered by steep mountain ranges unsuitable for urban development, barren and covered in treeless grasslands (Figs. 1a-d). Consequently, most of the lowlands and lower strata are now converted into dense urban sprawl which has little left in terms of native species.

As of 2017, only about 25% of the total land area has been developed, with the remainder of Hong Kong left in relatively undeveloped state, designated as protected areas in various categories (e.g., more than 45% as country parks). But just above the most densely populated areas of Hong Kong, forest vegetation still persists and is poised to make a comeback. The reasons for this are both historical and ecological.

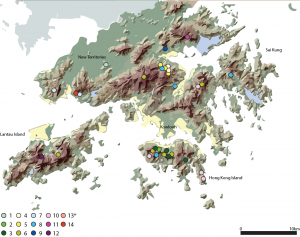

Fig 1a Map of Hong Kong showing elevation gradients and relative distribution of Oak species from known locations. (see Table 1 for details; distribution of Q. myrsinifolia not indicated on map as it is common throughout Hong Kong). 1: Q. acutissima; 2. Q. acuta; 3. Q. bambusifolia; 4. Q. bella; 5. Q. blakei; 6: Q. championii; 7. Q. chungii; 8. Q. edithiae; 9. Q. fabri; 10. Q. glauca; 11. Q. hui; 12. Q. litseoides; 13. Q. myrsinifolia; 14. Q. variabilis. (Map modified from www.hkss.cedd.gov.hk).

Reforestation of Hong Kong’s barren hills has always been an aim of successive administrative bodies, but its drivers have evolved over time. In the 19th century, health and aesthetics were the prime reasons, while in the 20th century soil erosion and water supply needed to be brought under control as Hong Kong experienced a population boom and intense urbanization (Corlett 1999). Nowadays, efforts have coalesced into incorporating ecological restoration as an integral part of urban slope and water management systems. Although there is some debate on how the potential natural vegetation (PNV) of Hong Kong should be classified, the most recent views suggest that the lowlands (below 500 m) should be considered as largely tropical while the vegetation above 500 m should be considered as subtropical (Dudgeon and Corlett 2004).

Fig 1b Oak habitat on Hong Kong Island. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Seasonal variation in precipitation in Hong Kong can be extreme (ranging from monthly averages of 24 mm in January to over 400 mm in June). Precipitation is also dependent on spatial variation: high mountains such as Tai Mo Shan (957 m) can receive up to 3,000 mm annually. Natural sponge and regulatory functions of intact upland vegetation are crucial in preventing flooding and landslides that endanger densely populated areas and infrastructure at lower elevations. As a consequence, a complex management system of slope maintenance and monitoring is in place in urban areas, consisting of individually registered trees, drainage channels and gullies, staircases and walkways. Many of the latter are open for recreational purposes and allow easy access to steeply forested hillsides, offering spectacular views over the city and of course, easy access to some of its fine oak species (Fig 1b-d).

Fig 1c TaiMoShan mountain forest. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Oak species and their modern-day distribution in Hong Kong

Today, most oak species and other Fagaceae in Hong Kong are found only in upland areas as disjunct populations or on isolated mountains (Table 1, Fig. 1a-d). It is not entirely clear to what extent this distribution pattern is natural, or if some species may have had a wider distribution which extended to include and connect mid- or even lower-elevations in pre-urban times. It is thought that the first clearings, burning and steps of habitat fragmentation in Hong Kong date back to 1,100-1,200 CE, suggesting that intact old-growth forests have not existed in Hong Kong for many centuries (Hau et al. 2005). If this is correct, it could mean that forest structure and species composition in the degraded and secondary forests we see today have little in common with the original pre-urban forest ecosystems. This is also suggested by ongoing work conducted at Kadoorie Farm and Botanical Garden (visit the homepage), which operates flora conservation, ecological restoration and forest replanting programs, aimed at understanding Hong Kong’s pre-urban forests in the hopes of rebuilding these.

Fig 1d View on Lam Tsuen from TaiMoShan. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Species performance tests in KFBG’s long-term plots and tree-planting sites highlight the difficulties in piecing together a native but grossly unknown forest ecosystem. Rebuilding Hong Kong’s forests requires a thorough understanding of the connection between the roles of temporally differential recruitment of species and the ecological space each occupies inside the system. Matters are complicated further by the fact that the original ecosystem that housed the more than 36 species of Fagaceae consisted of humid, closed canopy forests. Many of the larger mountains and hills in modern-day Hong Kong have been reduced to hot, windswept rocky grasslands – a hard place for any subtropical acorn to germinate.

Table 1 Properties and distribution of Oaks in Hong Kong.

Besides Quercus and other Fagaceae (23 species), Hong Kong is also species rich in families such as Lauraceae, Magnoliaceae and Annonaceae. Under natural conditions, these families co-occur, although species combinations will vary from site to site. In today’s forests, many of these species occur as relatively low-stature trees of modest diameters forming shallow, low-branching crowns. In some cases, like for Q. bambusifolia Hance, individuals even occur as shrubs or small treelets (Fig 4a-b). But individual trees in protected Feng Shui village forest plots, which can be hundreds of years old, and forest fragments in more remote sites (especially those in locations historically sheltered from fire), offer glimpses of what old-growth forest trees may have looked like. Not only do these sites contain rare elements of the original flora found nowhere else, but tree species like Q. blakei Skan (Figs. 6a-b) assume larger single bole diameters and develop different canopy architectures here, allowing for a more open, high-canopy forest. Contrastingly, some native tree species (e.g., Michelia spp.) that develop small understory crowns under closed canopy conditions develop wide-spreading dominant habits when grown on barren slopes (G. Fischer, KFBG, pers. comm). These are not just a result of growing-site conditions (open vs. sheltered), as combined growing trials have shown the effects different species combinations have on tree growth, crown architecture and crown development. Perhaps these patterns demonstrate that the many tree species known to make up the ancient forests of Hong Kong may have had very narrowly defined ecological roles and temporal optima in the system (e.g., species confined to ridges and crests, along creeks, on seaward exposed hillsides etc.). It also shows us that, although the oaks of Hong Kong may appear secure in the pockets where we find them today, the forest that they are a part of may be a long way off from growing and developing like it did in pre-urban times, and we need to learn more on how these drastic changes affect their genetic resilience and long-term survival.

Quercus in Hong Kong

A total of twelve species are listed as native to Hong Kong, with an additional species confirmed as having been introduced in the past (AFCD 2012). Here I also report a new record which brings the total to fourteen species. During fieldwork in 2015 I collected three individuals of Q. variabilis Blume in the New Territories. For each species recorded in Hong Kong, a small description and locality data are provided below (see also Table 1 and Fig. 1a). More data is available on each individual species page (see included links).

Quercus acutissima Carruth.

Medium-sized deciduous tree, up 15-20 m tall. Crown pyramidal and wide when young. Bark deep dark brown to grey brown, covered with deep cracks and lighter colored longitudinal fissures. Can attain large diameters of up to 1.6 m at breast height. Wood light yellow. Twigs yellow brown to olive green, glabrescent. Leaves leathery but thin, oblong-lanceolate, ranging from 10-20 cm long and up to 2 cm wide. Leaves bright green above, but dull pale below. Young leaves reddish, soft, covered in long whitish felt-like hairs. Cups covered in long, raised, incurved bracts, covering up to 2/3 of the nut. Fruits very showy and distinct. Nut deep dark brown, up to 2.5 cm long, 1.5-2 cm across. Flowering in April-May. Fruits maturing in two years. Occurring from lowland to upland (100-2,200m). (See Fig 2a-c). Read more

Fig 2a Q. acutissima acorn. Photo by © Francisco Garin.

Fig 2b Q. acutissima bark. Photo by © Thierry Lamant.

Fig 2c Q. acutissima leaves. Photo by © M. Timacheff.

Quercus acuta Thunb.

Medium-sized evergreen trees, up to 10-12 m and dbh of 30 cm. Can have a shrubby habit in cultivation. Crowns spherical. Bark smooth, covered in shallow fissures, dark grey to grey brown. Leaves dark green, glossy above, and yellow to pale yellow beneath, 5-18 cm long and up to 6 cm wide. Leaf base cuneate-rounded, apex acuminate, margins smooth and entire, wavy, rarely with any teeth. Cups covered in raised rings (5-8), covered in dense golden indumentum. Nuts oval to elliptic, warm orange brown, up to 1 cm across and 2 cm long. Cupules covering up to 1/3-1/2 of the acorn. Acorns clustered on long stalk. Flowering in April-May. Fruits maturing in one year. Occurring in low and mid elevations (300-1,100m). (See Fig 3a-d). Read more

Fig 3a Q. acuta acorns. Photo by ©Anke Mattern.

Fig 3b Q. acuta leaves front. Photo by © M. Timacheff.

Fig 3c Q. acuta leaves back. Photo by © M. Timacheff.

Fig 3d Q. acuta habit. Photo by © M. Timacheff.

Quercus bambusifolia Hance

Evergreen trees to 20 m tall. Young woody part covered in short silky hairs, but smooth when older. Leaves clustered near ends of twigs, narrow lanceolate to elliptic-lanceolate, 3-11 cm long and up to 2 cm wide. Leaves leathery, whitish below. Infrutescence very small, 5-10 mm, usually carrying only one single fruit. Cupule saucer-shaped, 5-10 mm × 1.3-1.8 cm, covering only the base of the nut. Cups covered in flat rings. Nut obovoid to ellipsoid, 1.5-2.5 cm wide and up to 1.6 cm long. Flowering from February-March, fruiting from August-November. Fairly rare species, occurring from low to mid elevations, up to a maximum of 2,200m. (See Fig 4a-b). Read more

Fig 4a Q. bambusifolia acorns. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Fig 4b Q. bambusifolia habit. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Quercus bella Chun & Tsiang

Large evergreen trees, up to 30 m tall. Often occurring in densely grouped clusters of many individuals. Known to mass fruit simultaneously in Sai Kung. Twigs grey brown, ridged or angular. Leaves oblong-elliptic to lanceolate, up to 15 cm long and 4 cm wide. Leaves light green to grey green, with age becoming thick. Leaf base cuneate and slightly oblique, upper half of leaf with serrate margin, apex acuminate. Cupules usually 2-3, disc-shaped, 5 mm long, and up to 3 cm across, covering only the base of nut. Cups covered in slightly raised rings, loosely covered in powder-like brown indumentum. Nut broadly oblate,up to 3 cm long with golden-like hairs when young, but smooth when mature. Acorns often wider than cup diameter, giving a swollen appearance appearance. Flowering from February-April, fruiting in October-December. Only at lower elevations up to 700 m. (See Fig 5a-b). Read more

Fig 5a Q. bella young leaves. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Fig 5b Q. bella acorns and seedling. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Quercus blakei Skan

Large evergreen forest trees, up to 35 m tall. Able to form large spacious crowns, but in shady forested gorges usually forming dense columnar crowns. When growing under dense shade, Bark grey, flaky and finely fissured. Twigs without noteworthy indumentum, but older woody part with dense lenticels. Leaf blade narrow ovate-elliptic to obovate-oblanceolate. Lamina up to 19 cm long and up to 2 cm wide, thin to somewhat leathery, with clear red indumentum in young phase. Leaf base cuneate, apex acuminate, upper 2/3 of leaf serrated. Cupules usually solitary or in pairs. Cups covered in flat rings (6-7), saucer-shaped to forming a shallow bowl. Up to 1cm across and 3 cm long, covering only the base of the nut. Nut ellipsoid-ovoid, 2.5-3.5cm long and and up to 3 cm wide. Flowering in March and fruiting from October to December. Rare. Found in local isolated pockets from lowland to high elevation (100-2,500m). (See Fig 6a-b). Read more

Fig 6a Q. blakei bark. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Fig 6b Q. blakei leaves. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Quercus championii Benth.

Evergreen and ranging from stout 2-4 m- to 20-m-tall trees with diameters up to 1 m. Crowns irregular, bushy to somewhat plume like due to leaf arrangements. Bark very roughly scaled, coming apart in patches, grey to grey brown. Sapwood pale white to light yellow. Twigs with longitudinal fissures, covered in dense grey-brown stellate indumentum, but older woody parts smooth. Leaves clustered on end of branches, crowded toward twig apex. Leaves obovate, sometimes oblong to elliptic but always with distinctly revolute margin, making for easy identification in Hong Kong. Length of leaves between 3.5-13 cm, up to 4.5 cm wide, sturdy and thick leathery. Undersides pale with whitish-orange stellate hairs. Leaf base cuneate, apex with a short blunt tip. Cupules arranged in groups of 3-10. Cups covered in raised rings, with dense feltlike indumentum. Cupules bowl shaped, 4-10 mm across and up to 2 cm long, enclosing up to 1/3-1/2 of the nut. Nut broadly ovoid to oblate, 1.5-2 × 1-1.5(-1.8) cm, hairy when young, glabrescent, base and apex rounded; scar 4-5 mm in diam., flat. Flowering from December-March and fruiting from November-December in the following year. Spread throughout lowland and up to the edge of highland forests (100-1,700m). (See Fig 7a-b). Read more

Fig 7a Q. championii acorns. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Fig 7b Q. championii habit. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Quercus chungii F.P.Metcalf

Evergreen trees up to 15 m tall. Twigs and young branches covered in dense brown felt-like indumentum. Older woody parts smooth. Leaves elliptic to rarely obovate-elliptic, up to 2-4 cm wide and up to 12 cm long. Thick, rough to the touch, covered in greyish or reddish-brown stellate hairs on both sides when young. Leaf base cuneate to somewhat rounded, apex acute to caudate with an elongated tip, margin sometimes serrulated towards apex. Cupules arranged in groups of 2-6, saucer-shaped, 1.5-2.3 cm long and up to 8 mm wide. Cups covered in flat imbricate scales. Cupules only covering the base of the nut, interior and exterior covered in grey-brown indumentum. Nut broad oblate, ranging from 1.5 cm wide and up to 1.7 cm long. Lowland species, occurring between 200-800 m. Flowering from April-May, fruiting from October-November. Read more

Quercus edithiae Skan

Medium-sized evergreen trees up to 20 m tall. Twigs slightly angular, glabrous, covered in lenticels. Bark smooth, often with lenticels arranged in rings or lines. Leaves oblong-elliptic, sometimes slightly obovate, 5-16 cm long and up to 6cm wide, leathery, bright red when flushing. Leaf base cuneate, apex with a distinct blunt tip, upper 1/3 of leaf sometimes with serrulate margin. Cupules generally arranged in 3-4 together. Cups covered in raised rings, covered with golden felt-like indumentum. Fruits usually single or in pairs. Cupules bowl-shaped, 1.2-1.5 cm across, and up to 2.5 cm, enclosing up to 1/4-1/3 of the nut. Indumentum outside erect, velvety orange brown and inside long, adpressed and orange brown. Nut ellipse to cylindrical, up to 4.5 cm long and 3 cm across. Nuts usually with a swollen appearance and wider than cup, giving a distinct appearance from most other species in Hong Kong. Flowering in April-June, fruiting in October-December. Occurring from low- to mid- elevations but nowhere above 1,800m. (See Fig 8). Read more

Fig 8 Q. edithiae Skan. Photo by © Jinlong Zhang.

Quercus fabri Hance

Deciduous trees to very large shrubs, up to 20 m tall. Bark grey brown to grey yellow, with fissures when young but sometimes becoming scale-like in older individuals. Leaves obovate to elliptic-obovate, 7-15 cm long and up to 8 cm wide. Both sides covered with short white to yellow-grey stellate hairs. Leaf base cuneate to somewhat rounded, apex obtuse. Leaf margin undulate, sometimes slightly serrate. Cupules generally only 2-4, cup-shaped, 4-8 mm across, and up to 11 mm long, enclosing up to 1/3 of the nut. Cups covered in flat imbricate scales. Nut narrowly ellipse to ovoid shaped, ca. 0.7-1.2 cm wide to 1.7 cm long. Flowering in April, fruiting in October. Occurring from lowlands to mid-elevation (100-1,900 m). Read more

Quercus glauca Thunb.

Evergreen trees up to 20 m tall. Crown generally wide and spreading, but dense. Leaves obovate to oblong-elliptic, 6-13 cm long and up to 6 cm wide. Leaves thick, leathery, showing scale-like whitish hairs, but smooth at later age. Leaf base round to broadly cuneate, with the upper half with small teeth. Leaf apex acute. Cupules bowl-shaped, 6-8 mm wide and up to 1.4 cm long. Enclosure of the nut variable, ranging from 1/3-1/2. Cups covered in flat rings consisting of fused scales. Nut ovoid to oblong-ovoid, or even ellipsoid. Acorns edible. Flowering from April-May, fruiting in October. Although Q. glauca is easy to distinguish from other oak species in Hong Kong, in the wider range where it occurs, it is very variable in appearance, leading to the general conception of it being a complex of species or subspecies that is yet to be investigated properly. (See Fig 9a-b). Read more

Fig 9a Q. glauca habit. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Fig 9b Q. glauca acorns and leaves. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Quercus hui Chun

Evergreen trees ranging from 15-20 m tall. Crowns dense and bushy. Bark smooth, grey to grey brown. Twigs and small branches covered with dense orange-brown curly hairs, but older sections glabrescent. Leaves slightly leathery, variable in shape from oblong-elliptic, oblanceolate to elliptic-lanceolate, 7-10 cm long to a maximum of 4 cm wide. Margins recurved, entire to sometimes slightly serrulate towards the apex. Infructescence mostly with 1-2 fruits only. Cupule variable from a shallow bowl to a flat disc. Cup 4-10 mm high and up to 3 cm wide, covering only the base of the nut. Exterior and interior of cupules covered with felt-like yellow-brown indumentum. Cups covered in raised rings. Nut big and spheroid, 1.5-2 cm wide and up to 2.5 cm long, densely golden tomentose when young. Flowering in April-May, fruiting from October-December. Only occurring in forests at lower elevations (300-1,200). Rare (See Fig 10). Read more

Fig 10 Q. hui acorns and leaves. Photo by © Jinlong Zhang.

Quercus litseoides Dunn

Small evergreen trees, up to 10 m tall. Twigs sparsely tomentose, glabrescent. Leaves with tiny petioles or more often completely absent. Species characteristic for Hong Kong in having fairly narrow (1-2 cm) but often very long leaves (up to 7 or 8 cm). Lamina obovate-oblanceolate, smooth, glabrous. Base wedge-shaped, margins entire and apex semi-rounded. Cupules free, often in twos, bowl-shaped, covering up to 1/3 of the nut. Cups covered in flat rings. Nut ellipsoid (1.5 × 1 cm). Generally rare throughout its range, known from only a few locations in Hong Kong. Occurring only at lower elevation zones. Flowering in January, fruiting in December. (See Fig 11a-b). Read more

Fig 11a Q. litseoides flowers. Photo by © M.Wan.

Fig 11b Q. litseoides habit and acorns. Photo by © M.Wan.

Quercus myrsinifolia Blume

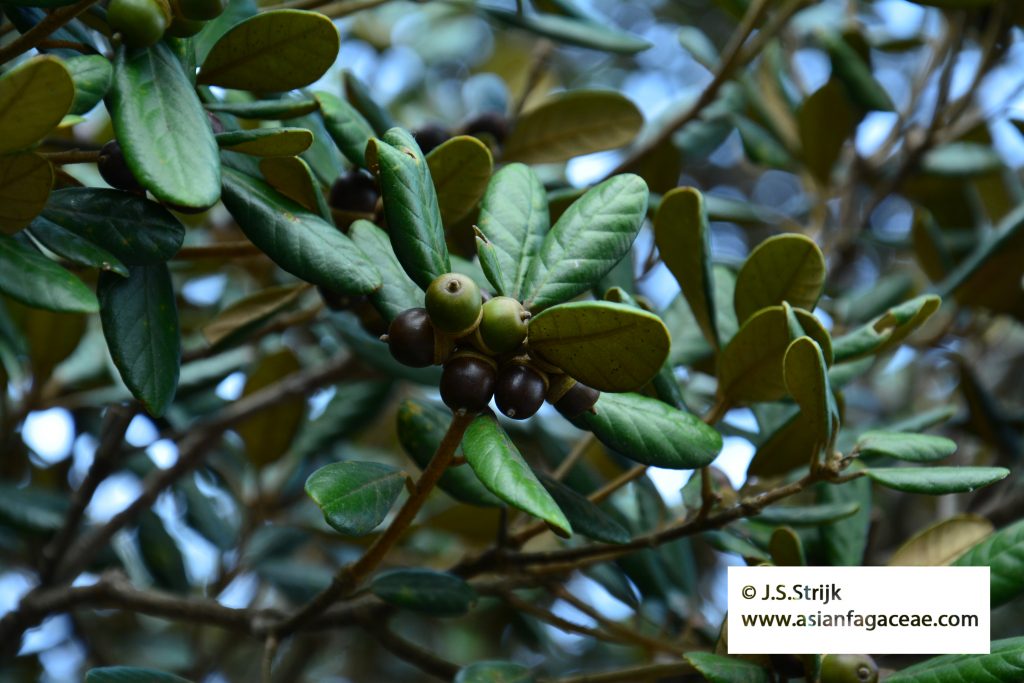

Evergreen tree, up to 15 m tall. Sometimes forming shrubby habit in cultivation. Crown shape often globe-like. Bark grey, thin, with small lighter colored fissures. Twigs smooth, covered in grey-brown lenticels. Leaves ovate to elliptic-lanceolate, 6-11 cm long and up to 4 cm wide. Undersides whitish, glabrous. Base of leaf wedge-shaped to rounded. Underside whitish, but dark grey when dry. Leaf base cuneate-subrounded, apex acuminate-caudate and upper half of leaf serrulate. Young leaves sometimes deep dark red. Cupule cup-shaped, 2 cm long and up to 5-8 mm wide. Cup enclosing up to 2/3 of the nut, which is ovoid-ellipsoid, 1.4-2.5 cm long and up to 1.8 cm wide. Cups covered in raised rings. Generally flowering in June, and fruiting around October. Widespread species throughout Hong Kong, but with variable morphology across the wider region. Found between 200-2,500m (See Fig 12). Read more

Fig 12 Q. myrsinifolia fruits and leaves. Photo by © Jinlong Zhang.

Quercus variabilis Blume

Deciduous tree, up to 25-30 m tall. Large, spacious open crowns, distinct from other oak species in Hong Kong. Stem diameter up to 40-60 cm, with thick, cork-like bark with deep fissures. Wood a deep yellow to yellow brown. Twigs greyish brown to grey, smooth. Leaves dark green above, silver below, simple with dentate margins, each secondary vein ending in a hairlike, protruding tooth. Petioles 1-5 cm, leaves 8-20 cm long and 2-8 cm wide, with sharp apex and wedge-shaped to rounded base. Cupules are cup-shaped, 1 × 4 cm, covered in raised bracts and enclosing the nut up to 2/3. Bracts are recoiled backwards and down, with the nut becoming progressively more visible at maturity. Known from mainland sites to grow up to 3,000m, but in Hong Kong currently know from only one seaside location at lower elevation. Flowering in April-May, fruiting in September-October. (See Fig 13a-b). Read more

Fig 13a Q. variabilis fruit. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Fig 13b Q. variabilis habit. Photo by © Joeri S.Strijk.

Acknowledgements

My research projects allow me the great pleasure to explore and study oaks and other Fagaceae throughout Asia. I would like to thank my collaborators and friends at Hong Kong University (Saunders Lab), Kadoorie Farm and Botanical Garden and Hong Kong’s Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department for consistently providing a supporting and welcoming research base on my visits to Hong Kong. I would also like to thank Mathew Wan and Joe Lau for their insights and enthusiasm in exploring and studying the Hong Kong flora. This Hong Kong Oak study was financially supported by Guangxi University, Guangxi Province and the National Science Foundation of China.

Works cited

AFCD. (2012). Check List of Hong Kong Plants. Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, Hong Kong Government, Hong Kong, China.

Chong, K. Y., Tan, H. T. W., & Corlett, R. T. (2009). A checklist of the total vascular plant flora of Singapore: native, naturalised and cultivated species. Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore.

Corlett, R. T. (1992). The Naturalized Flora of Hong Kong: A Comparison with Singapore. Journal of Biogeography, 19(4), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.2307/2845570.

Corlett, R. T. (1999). Environmental forestry in Hong Kong: 1871–1997. Forest Ecology and Management, 116(1–3), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(98)00443-5.

Dudgeon, D., & Corlett, R. (2004). The ecology and biodiversity of Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Friends of the Country parks.

Department of Environmental Resources Management, Hong Kong S.A.R. Government (2008). Update of Terrestrial Habitat Mapping and Ranking Based on Conservation Value. Hong Kong.

Hau, C. H., Dudgeon, D., & Corlett, R. T. (2005). Beyond Singapore: Hong Kong and Asian biodiversity. TREE, 20(2), 281–282.

Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K., eds. (1992) Flora of Thailand, Vol. 9, part 3: Fagaceae. Royal Forest Department, Bangkok.

Shum, T.-W. (2015). The status of natural succession in lowland secondary forests of Hong Kong. University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5353/th_b5674079.

Soepadmo, E., & Steenis, van C. (1972). Fagaceae. Flora Malesiana-Series 1, Spermatophyta, 7(1), 265–403.

Strijk, J. S. (2019a in preparation). Flora of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam – Fagaceae (in preparation for 2019). Edinburgh & Paris: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris.

Strijk, J. S. (2019b in preparation). Flora of Singapore – Fagaceae (in preparation). Singapore: Singapore Botanical Garden.

Strijk, J. S. (2016). ASIANFAGACEAE.COM – The Complete Database for Information on the Evolutionary History, Diversity, Identification and Conservation of Over 700 Species of Asian Trees. Retrieved from www.asianfagaceae.com/

Trehane, P. (2007). The Oak Names Checklist. Published on the internet http://www.oaknames.org. Retrieved August 20, 2001, from http://www.oaknames.org

Yi, W. Z., and Raven, P. H. 1999. Flora of China,Vol. 4. Cycadaceae through Fagaceae. Science Press, St. Louis, Missouri Botanical Garden, Beijing, China.

Other species of Fagaceae found in Hong Kong:

Lithocarpus

Lithocarpus attenuatus (Skan) Rehder Read more

Lithocarpus corneus (Lour.) Rehder Read more

Lithocarpus elizabethiae (Tutcher) Rehder Read more

Lithocarpus fenestratus (Roxb.) Rehder Read more

Lithocarpus glaber (Thunb.) Nakai Read more

Lithocarpus haipinii Chun Read more

Lithocarpus hancei (Benth.) Rehder Read more

Lithocarpus harlandii (Hance ex Walp.) Rehder Read more

Lithocarpus irwinii (Hance) Rehder Read more

Lithocarpus iteaphyllus (Hance) Rehder Read more

Lithocarpus konishii (Hayata) Hayata Read more

Lithocarpus litseifolius (Hance) Chun Read more

Lithocarpus macilentus W.Y.Chun & C.C.Huang Read more

Lithocarpus quercifolius C.C.Huang & Y.T.Chang Read more

Castanopsis

Castanopsis carlesii (Hemsl.) Hayata Read more

Castanopsis concinna (Champ. ex Benth.) A.DC. Read more

Castanopsis eyrei (Champ. ex Benth.) Hutch. Read more

Castanopsis faberi Hance Read more

Castanopsis fargesii Franch. Read more

Castanopsis fissa (Champ. ex Benth.) Rehder & E.H.Wilson Read more

Castanopsis fordii Hance Read more

Castanopsis lamontii Hance Read more

Castanopsis kawakamii Hayata Read more

Castanopsis sclerophylla (Lindl. & Paxton) Schottky Read more